May Day

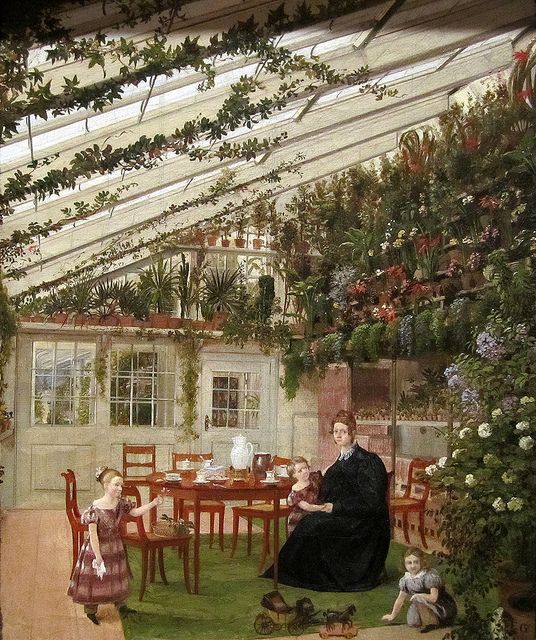

May Day has been celebrated throughout the United Kingdom for centuries, although the festivities had started dying out a bit during the Regency. Still, Jane Austen mentions the neighborhood maypole blowing down in a storm, and the Hampshire Chronicle speaks at length about the celebrations in 1815, which involved couples dancing in or on a flower-laden bower (I couldn’t picture this from the description). See this blog for more about these citations. Other parts of May Day included crowning a May Queen, and the more obscure practice of leaving small May baskets of treats for people.