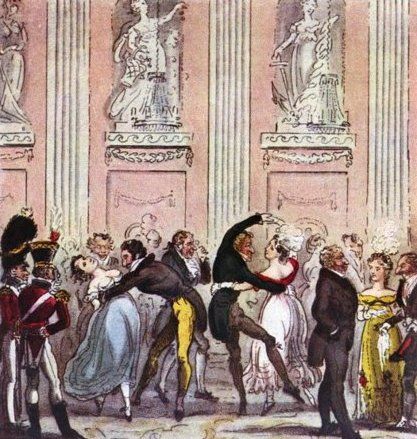

“Auld Lang Syne”

You probably know that “Auld Lang Syne” was written by Scottish poet Robert Burns, but you may not know that he was taking some of it from an older folk song. He’s the one who retooled it into its current version and popularized it in Scotland, and then, once he had it published, in England. Regency revelers sang his poem on New Year’s Eve just as we do, although it may not have been sung to the same tune. Still, it’s amazing how far back the sentiments go. One precursor to his poem that uses similar verses was published in 1711!