Frost Fairs

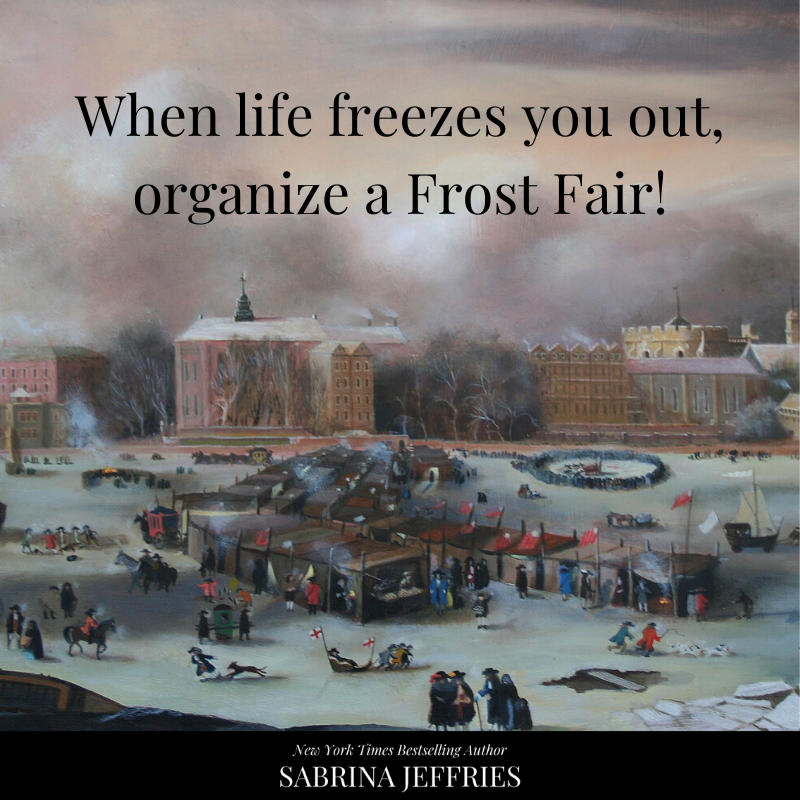

So, if you’re a fan of the Regency period, you’ve probably heard about the London Frost Fair of 1814, when the Thames froze for four days, and people set up fairground booths on the ice. They even led an elephant across! But you may not know why it happened. It was partly due to the Little Ice Age, which engulfed many parts of the world from around 1600 to 1850. Since seven possible causes have been postulated for why that happened, we won’t get into that. The upshot is that the Thames was wider and slower then, so the decrease in temperatures resulted in a number of frost fairs being held during those centuries. London Bridge also had more pilings that dammed up the river with ice in winter.

After 1814, the Thames never saw another Frost Fair. London Bridge was rebuilt with less pilings. The river was embanked, which helped it flow more freely. And the weather grew warmer. Don’t you wish you could have experienced a Frost Fair on the Thames? I do!