The Truth about Marriage

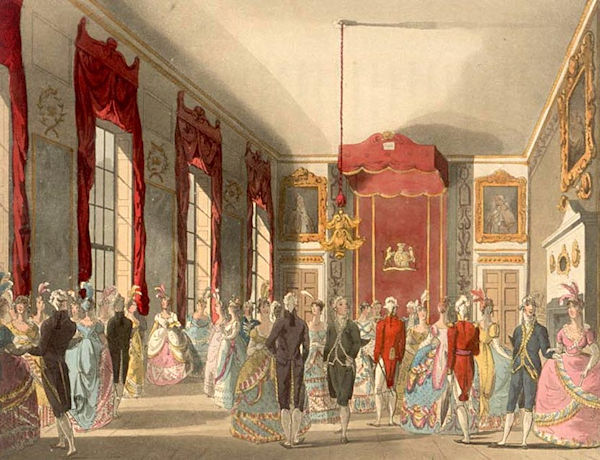

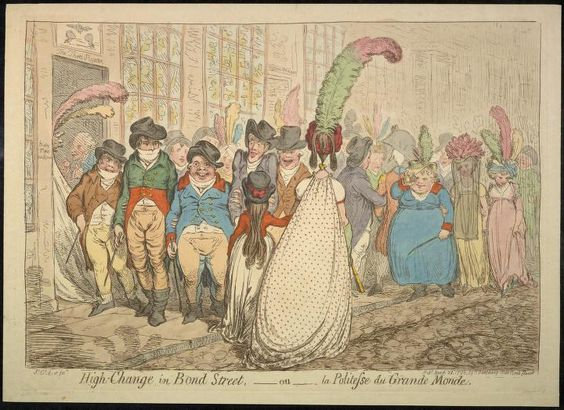

My favorite part about doing research is stumbling over real stories of people. We tend to have misconceptions about the past: Everyone married only once and died young is a popular one. The last part in particular isn’t true, because the data used to determine life expectancy factors in all the many children who died of illnesses that we now vaccinate for—polio, smallpox, measles, mumps, rubella, etc. Here’s a case in point. The Duke of Leinster and his wife, one of the famous Lennox sisters, Emily, had 19 children. Of them, only 10 survived to adulthood. One died on the day of her birth although I couldn’t discover if she was stillborn. The last child was actually Emily’s illegitimate son by William Ogilvie, the tutor to her eldest son, although her duke husband claimed him. After her husband’s death, she married Ogilvie and had 3 more children, only two of whom survived to adulthood. She lived to the ripe old age of 82 and he died at 91. He was 18 years younger than she, but they lived happily together for 40 years. She must have been one amazing woman, and he must have been an amazing man. The woman bore 22 children in all. How incredible is that?